I remember quite clearly the first time I visited

North Africa—it was a school trip to Tunisia. But somehow I don’t remember that

much novelty to the visit. Oh sure, I spent a lot of time kissing a boy I had a

huge crush on, and I drank too much (there is no drinking age in Tunisia,

certainly not for blonde American girls with cash in their pockets), and that

was new, or new-ish, and certainly exciting.

But there were also roman ruins, and franco-italian-arabic tourist

dialects, and delicious bread, and the Mediterranean. The flight from Rome was only a few hours,

but it seemed closer.

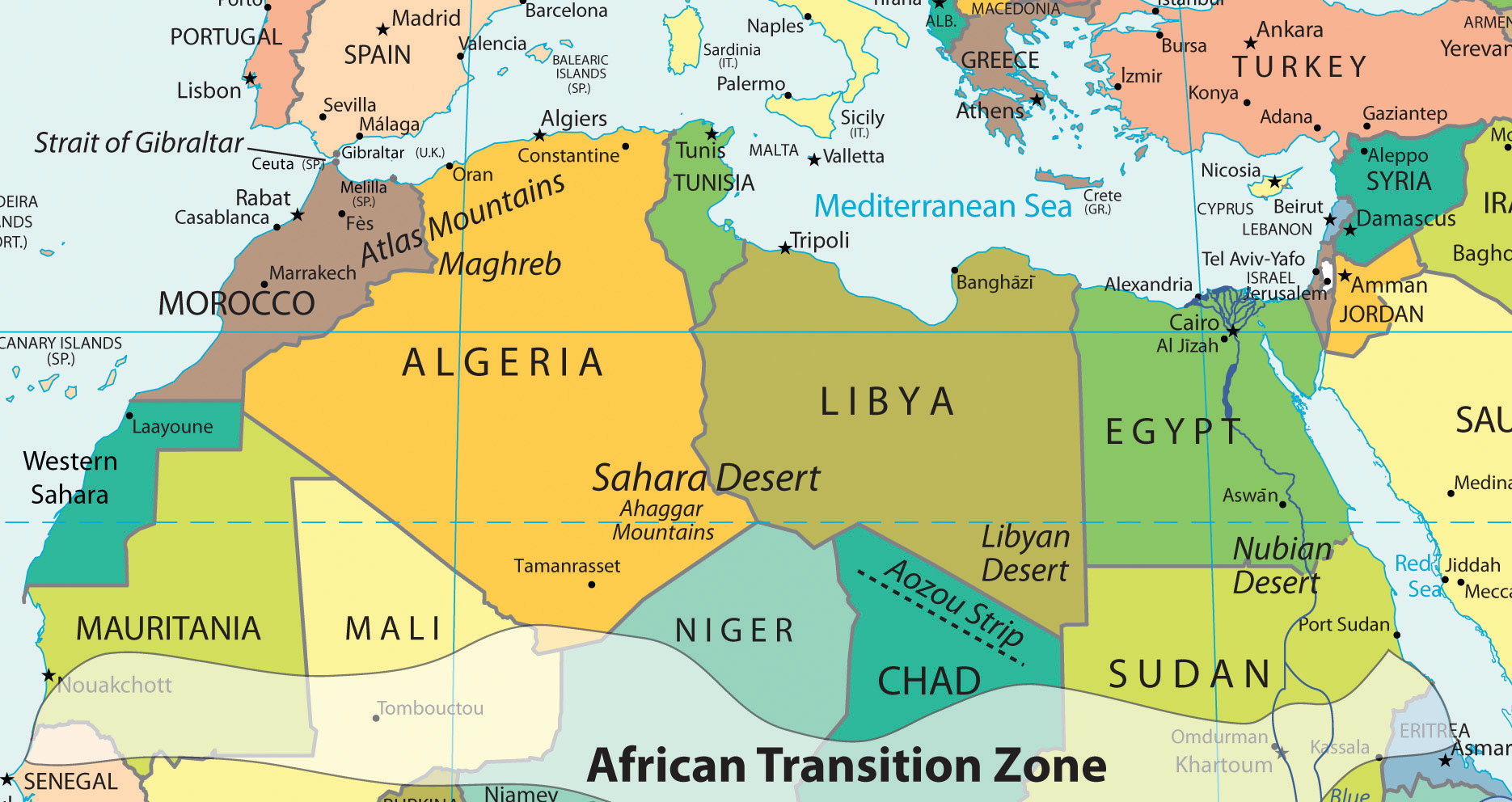

A map will show you that Italy and Morocco and Libya and Algeria and Tunisia and Egypt are 6 countries on two different continents. But I once accidentally drove into Libya from Tunisia, the (main) Prime Minister of my youth died at his home in Tunisia, and, as a child, classmates’ fathers commuted to Libya, a former colony of Italy.

You could—any many have—row a boat from Kelibia to

Sciacca. And in Rome it has always been possible to find delicious, authentic

Tunisan couscous.

My father had a fetish for the food of the Maghreb.

We would eat at a Libyan-owned fish restaurant in Trastervere once a month, for

Sunday lunch, after dinner, when I was a teenager. It was with my father, too,

that I first visited the Couscousterie on the bad side of Testaccio.

I do remember being thrilled by the idea of

visiting Tunisia, I thought certainly this was one place my father hadn’t

been-- I hadn’t ever heard any stories of it. And, he hadn’t been to Tunisia,

but of course, I learned, he’d been to Morocco (where he slept in a bath tub in

a falling down palace), and Algeria (When? Why? I’m still not sure), and he

couldn’t say that he hadn’t been to Libya.

For me, these were the “next countries over”, the

easy exotic, like going to Mexico from

the United States.

The last time

I was in North Africa was the summer of 2001. A few weeks after I left,

there was a bombing in Casablanca. And

then of course, 6 weeks later was 9/11.

I never planned not to go back. But now I don’t know when I will. Not because

of 9/11, but because of Benghazi. And it makes me second guess what

semi-dangerous place I might ever venture into again.

My first memory of awareness of terror and danger

and bombing and threats is from quite a young age: I moved to Italy during Gli

Anni di Piombo. There was the Red Brigade, the Mafia, and Abu Nidal. And, one

day, my mother told me I couldn't ride the bus to school. Nor the next day. My

mother said that the other children might be hurt if someone tried to kill me.

Of course, we never used the word "kill"-- it was "death

threat" or "blow [something] up".

In those days the Embassy, an old Palace the U.S.

had commandeered in the aftermath of the Second World War, was guarded by a

long iron gate and a few marines standing duty. You showed your identity card,

at the gate, perhaps explain your reason for visiting, and would then be waived

across the cobblestones to the reception hall, where there was an actual

appointment book, and telephones, and a switch board. It was only once inside

the Embassy that your identity and appointment might actually verified,

confirmed.... or refuted.

After a friend died in a bombing, I asked my

mother what the iron gates could do to keep us safe. She said that no one would

be foolish enough to attack an embassy, or our home.

My mother had took special driving classes, and

always checked under the car if it had been parked outside, unattended, for a

while. There were ways to walk and things to be aware of that I and my embassy

friends knew form an early age. We learned Italian fluently, some Arabic, a

smattering of French. We were expected to be the best and the brightest, but

also to learn everything we could about where we were, to try to understand it

in as many different ways as we could. And then, there was always the embassy

if worse came to worst. And stick together.

It wasn’t polite, or safe, to be an arrogant,

ignorant, oafish, superior American alone, but together, we were invincible.

And besides, only really crazy people really hated America (secretly, we all

knew, we really were the best. And we could show that by being polite,

respectful, and friendly). And the crazies were disorganized, young, and

persuadable; ideology would burn out. A sort of lone-gunman theory of

terrorism.

When we came back to Italy in the late 80's,

getting into the Embassy was much harder, the marines much stricter about ID.

And the gate at our house had been beefed up, and there was always a car of

policemen out front, and motion dictators caught me sneaking through the garden

to break curfew, once I got older. And sometimes there was a helicopter overhead.

I didn't really think Italy had gotten more dangerous-- if anything, it seemed

safer. No more Prime Ministers being murdered, no more CIA station chiefs being

kidnapped. It seemed as though the crazies had burned themselves out, and

at the same time, we were being better taken care of, more protected. Safe.

In retrospect, the Beirut bombings must have prompted

the extra security I experienced, and American “symbolic” security actually

decreased: Embassies were bombed again in 1998.

But from the standpoint of today, it seems easy to dismiss those as

anomalies: Osama Bin Laden was responsible for that attack, after all. If you

had asked me 2 years ago what to do when travelling overseas, and cared for

whatever reason, I would have said

confidently, perhaps with some nostalgia,

“Get to the Embassy”.

I've always thought of our embassies and consulates

as safe havens, and felt certain that if I went, they would take me: that they

would always be my home and family.

And, I imagine, the personnel-- U.S. government officers, civil

servants, contractors-- who died last

year in Benghazi must have thought sort of the same thing.

From what I’ve read, they’ve done everything my

mother always told me to do, from the best of their abilities/positions: learned Arabic, asked for help, met with the

locals, grabbed a gun.

To the last point: I know that when people sign up

for the military or are military contractors for the CIA there is some

acceptance of potential death And, certainly, the Foreign Service officers

killed would have been receiving hazard pay.

But, they were Americans. The best and the

brightest, who had done everything right.

And we are a country that famously says “no man left behind”.

On the ground, support was asked for, and on the ground,

Americans acted like Americans and came to help their compatriots. But no support arrived form the United States.

I don't have a recipe, or a pattern, or a photo for this one. Being

aware, communicating, making your own help, and then asking for more help is

strength, not weakness. But what do you do when help doesn't come?

No comments:

Post a Comment